When April with its showers sweet

Geoffrey Chaucer, the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales

Has pierced the drought of March root deep

[…] Then folk long to go on pilgrimages,

And palmers to seek foreign strands,

To distant shrines, known in various lands

And specially from every shire’s end

Of England to Canterbury they wend.

We stayed last night with my cousin Frances and her family in the ancient Kentish village of Wye, and she was to walk this first day with us, keeping us company and seeing us off in style. Her husband Gareth gave us a lift into Canterbury, and we walked towards the cathedral gate, the golden sandstone of the tower over the great crossing rising before us at the end of the cobbled street, glowing in the early morning sun.

My pilgrim credential got me not only free entrance to the cathedral, but also the first two stamps in the little booklet which will be studded and stuffed with stamps collected at each day’s end by the time I get to Rome. Frances, as a local, was allowed in with her annual pass, although Stephen paid the £18 entrance fee (not grudging it, because it costs £30,000 a day to keep the cathedral going). The Canadian woman on the ticket desk (bizarrely, a recent forensic pathology graduate) took us through the gateway in person to show us where the Via Francigena starts, at a slab of stone just inside the cathedral’s main gate. The slab is carved with a little chubby pilgrim figure, the Francigena symbol that I will follow for two thousand kilometres southwards.

Canterbury Cathedral is a fanfare of a beginning to the road to Rome, and it would have been unforgivable not to have visited it properly before leaving. Founded by Augustine on his mission from Pope Gregory I to convert the Anglo Saxons to Christianity in 597, it is one of the oldest Christian structures in Britain. On entering, the soaring nave takes one out of oneself and leads the eye through the choir to the high altar,

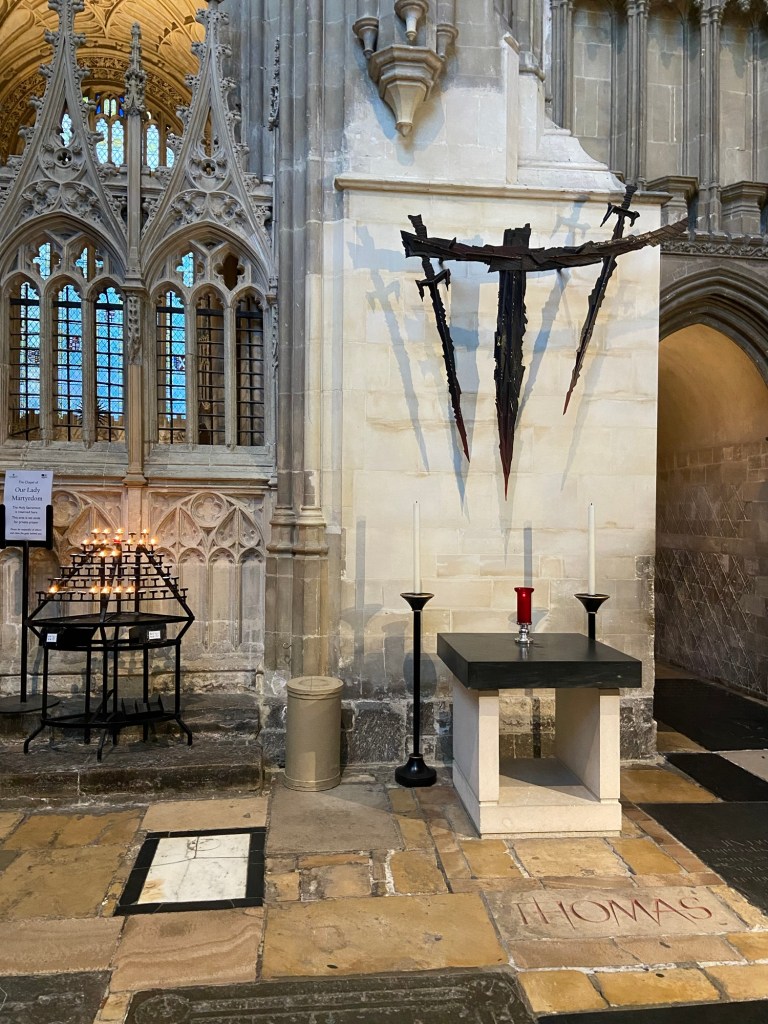

but we made our way first to the shrine marking the place where the troublesome priest Thomas à Becket was murdered in 1170. Behind an inlaid stone marker on the polished flagstones hangs a rough bronze sculpture, three jagged, stylised blades suspended above the Altar of the Sword Point.

An ornate golden casket covered all over with jewels originally held the bones of the St Thomas behind the high altar in the Cathedral’s Trinity Chapel. This was the centre of the Saint’s cult, and the focus of pilgrimage throughout the Middle Ages, when a steady stream of the sick and weak came to pray to St Thomas for healing. Their stories are commemorated in a dramatic series of ‘Miracle Windows’ complete with figures vomiting blood on their sickbeds, being exhorted to donate large sums of money to the church in order to be healed.

The shrine stood until 1538, when as part of the Reformation purges, Henry VIII ordered it broken up, the St Thomas’ bones destroyed, and all mention of his name obliterated. Today a single candle burns in the empty chapel on the flagstone floor in the place where the shrine once stood.

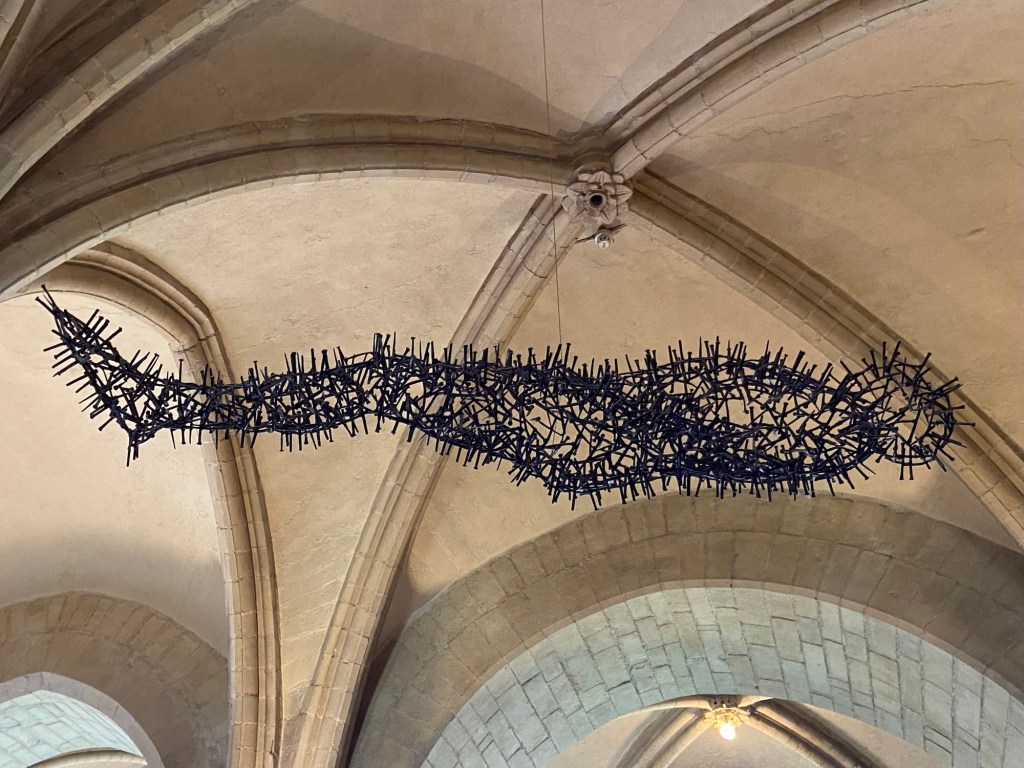

On down into the Crypt, a shadowy, suggestive place with low vaults and pillars holding up the great edifice above. I briefly joined in the intoning of a psalm in a chapel at the far end led by a cassocked cleric, while Stephen contemplated Antony Gormley’s iron sculpture, ‘Transport’.

Iron nails from the Cathedral’s roof form the compelling shape of a floating body, just over two meters long. The nails pass from the outside inwards, and the inside outwards. The sculpture is suspended in perfect balance from a single cord above the place where Thomas à Becket’s first tomb was built.

And so on outwards into the sun and air, and the cherry trees in full blossom against the freshly-cleaned stone of the Cathedral. The entire building had been swathed in scaffolding and plastic for eight years as the cathedral underwent a £25 million restoration project, completed in 2022. We took some commemorative pictures by the stone, to mark the occasion.

It was ten o’clock — the moment had come at last to get underway. I consulted the map on my phone for the first time. I needn’t have bothered though, since the signage was impeccable, and (dare I say it), unmissable.

The signposts took us past the abbey of St Augustine and on via a small detour to the Church of St Martin, at first sight unassuming, but in fact, the oldest church in the English-speaking world.

It is older even than the Cathedral, being founded during the Roman occupation, and successive phases of building were visible in the walls as we circumnavigated the outside of the church, from the narrow horizontal Roman brickwork (300s) to the Saxon flint (600s), from 12th century extensions to the 14th century tower.

My eye was caught by the gravestone of poor Laura, of whom all that is recorded is her Christian name, and the fact that she is “WAITING” for her husband (who had several lines of description himself). The gravestones were being industriously cleaned by an army of volunteers, the latest in 1400 years of people who have cared for and tended this church and its churchyard. They said that unfortunately we couldn’t go into the church itself because it was closed for a ‘private tour’, so we stood on the steps and admired the last view of the towers of Canterbury Cathedral, already surprisingly far away to the north-west.

We struck out immediately across the country roads and tracks of the Via Francigena, following here the North Downs Way over the chalk, flint and chert of wide-open arable fields, heading for Shepherdswell at day’s end, and Dover beyond.

The dire meteorological prognostications of earlier in the week had come utterly not to pass. We were treated to wall-to-wall sunshine for the whole route, as we chatted, passing between the banks of sunken lanes lined with ferns,

and delicate wood anemones, white flowers trembling on their fragile stalks in the slightest breeze, earning them their common name of ‘windflowers’.

The first hamlet we came to was Patrixbourne, named both for the rich Norman Patric family that held the manor (now hidden behind ultra-private gates and forbiddingly thick woods), and the chalk stream that runs through it, the Nailbourne. This stream was originally navigable, and the settlement had been established in the fifth century by invading Jutes, who left their mortal traces in 90 graves over a period of 100 years, bowing them to have been a statuesque race of men six foot tall, their grave goods proving them to have been rich and aristocratic.

The Patrics gave us our first flavour of the Norman architecture in which we will immerse ourselves over the coming days in the churches of France, in the form of the small but highly decorated church of Saint Mary, built by the family in the 12th century to replace an original Saxon church which they had had torn down.

The stone detailing over the elaborately-carved doorway was the thing that immediately struck us,

But a closer look at the door jambs reveal fainter traces of carved lines, crude sundials functioning as clocks to show the time of Mass.

Leaving the village behind we struck out once more over the flinty fields, encountering massive lumps of flint bigger than I had ever seen.

The path ran parallel to the dual carriageways of the A2, a constant rumble of cars and lorries that we hardly noticed after a while, being instead deep in constant conversation, and stopping stock still transfixed by the sound of the larks fluttering overhead, singing their unmistakable song as they rose higher and higher.

One giant field had been left to wildflowers, and amongst the skeletal remains of last year’s wild carrot and knapweed, the first of the cowslips showed their bright selves.

The sky was an incredible, joyous blue, set off both by wisps of cirrus clouds 23,000 feet above our heads, and also, in the few hedges that there were in the vast fields, by the white flowers of blackthorn.

Names of places on the map often build anticipation (I recall the excitingly-named Wenlock Edge on the End-to-End walk which turned out to be 18km of sheer unremitting drudgery). So I had been looking forward to Womenswold. I had built up in my mind the idea of some kind of beguinage, surely an inspirational, enlightened female community.

But no. I walked several times past a bramble-covered ruin, looking at it out of the corner of my eye and willing it to turn magically into a Harry Potter monument like that in Godric’s Hollow. It did not. Research this evening has revealed the disappointing fact that the name ‘Womenswold’ is a corruption of ‘Wymelyngewolde’ — ‘the forest of the people of Wimel (a man’s name). Sigh.

However between the hamlets (mostly exceptionally picturesque with lovely Kentish detailing like shaped tiles like scales in the sides of the houses, and scattered oasthouses) there were little tracts of woodland, where flowered great clumps of blue anemone blanda, garden escapees, and sweet violets, amongst the twisted roots of embattled ash trees.

By 2pm we were on the outskirts of Shepherds well, welcomed by Jackie and her huge 12-yr old English shirehorse, 19-hands tall and about to embark on a dressage career. The long white hair on his giant hoofs as they preceded us up the North Downs Way were as massive as polar bear paws.

Jackie was a Goldilocks of a horsewoman, her paddocks housing not only the most enormous of horse breeds and mid-sized mares, but also the tiniest, Dexter and her minute foal, coming scarcely higher than my knees.

I let myself into the church at Shepherdswell in search of the stamp to show I had passed through. The contrast in the simple structure with the gothic glory we had left behind in Canterbury was striking. I found both impressive in their own way.

Here in the churchyard, instead of the monuments and shrines to Kings and Saints, was a thick carpet of primroses, and a tiny 18th century headstone commemorating the eleven months on this earth of Thomas Friend, and the day he left it, almost exactly 226 years ago.

And that was the end of the first, very pleasant stage, 18.5 highly convivial and very enjoyable kilometres. My feet in the new shoes felt great, but my knees a little tired, despite not carrying any weight. They’re going to have to do better than that. I had walked with one pole only because of soreness in my arm, but when I have the full weight of my pack tomorrow I am going to need both!

Stats for the Day:

Distance: 18.31

Climb: 294

A glorious day for a glorious walk. And a glorious woman. Bonne chance!!! Enjoy lovely Kent. Xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

It feels all glory today! But weird being at the Port of Dover on the wrong side of Brexit.

LikeLike

What a fabulous start for you! I hope your shoulder has settled and remember to speak Kind Words to your not-as-strong but just-as-willing knee xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

🫡 everything is working surprisingly well so far. Knees, feet, shoulders, all present and correct! They have listened to the Kind Words

LikeLike

Hi Sophie, For some reas

LikeLiked by 1 person

Helloooo ?

LikeLike

I’m excited for you. I was talking to a friend this morning about Thomas a Becket and was able to share your photos and read your blog aloud. (For the third time of writing! I can’t seem to comment from my phone!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a brilliant coincidence… and how annoying!

LikeLike

oh my word! How fortunate to be following you. I will be starting my walk from Canterbury on 4 June so am looking very forward to all your news and information. I think your writing is fabulous, so descriptive

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Jan — how kind!

LikeLike

What a wonderful start! I will carry on following you, as I shall trace your footsteps in just some more weeks. Keep on walking, bonne courage and buon cammino!

Christian

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much! And good luck with your walk.

LikeLike