I saw the evening sun light up a coppice of trees on the side of a hill. It occurred to me then that here was something more beautiful still and the idea formed of building a cathedral with trees

Edmund Blythe, on the formation of his project to create a living memorial to his fallen WW1 comrades-in-arms, 1940

When I woke up this morning, my feet were still prickling and sore from the bashing they had received yesterday, and I was in no hurry to get up. Today’s stage would take me through the vast forest of Saint-Gobain and finish in the spectacular mediaeval hilltop town of Laon, one of the highlights of the Francigena according to the guidebook, something to work towards today. I needed to pace myself, and try and look after my feet, whatever that means. I suppose in practice it means wearing clean socks, having proper rests if possible and taking my shoes off and giving my feet some air, swapping my socks over and placing my feet carefully without exception. According to the weather app there would be no rain today, just dull cloud, but I was not sure how well I could trust it, given that when I was sheltering from the cloudburst in the tunnel yesterday the app showed that the current conditions were fair.

I set off with various damp bits of laundry in the mesh outer pockets of my rucksack, having judiciously applied Compeed to various sore spots on my left foot. I think my right foot has made a Dorian Grayesque pact with the devil. It still looks like it has just come out of a beauty salon, whereas my left foot (the portrait in this scenario) looks like it belongs to a gargoyle.

However, both needed to walk up to 28 km today. I took a gigantic snort from a lilac bush as I left Les Bruyères, the village south of Bertaucourt, to see me on my way.

It was a still, calm day, perfect for quiet walking through what was billed to be a quiet day. A small herd of cows was lying down in a field and I hoped that didn’t presage poor weather, but it didn’t feel like it somehow. There wasn’t enough energy in the meteorological system.

I picked my way very carefully over the grassy road, tempting though it was to stride out, because the ground underfoot on these muddy paths is always quite uneven. I wasn’t concerned about falling, just with rubbing the sides of my feet and twisting the ankle a little. At the side of the path, backlit by a sun veiled with cloud, clumps of crosswort were coming into flower — a type of bedstraw.

The field path sped me to the eaves of the Saint Gobain forest. Once the property of the great Abbey of Prémontré it became a royal forest for Henry IV, who hunted boar, and red and roe deer that still inhabit it. During World War I the forest formed part of the Hindenburg Line, and its warren of trenches took heavy bombardment.

At the little car park where the logging road commenced, a warning sign announced that oak processionary moth was becoming a problem in these woods. There was a long list of things to do if you came across any — not touching them would be the most important one, and having a lukewarm shower (!) when you got home. I will definitely be doing that at my hotel in Laon. But a hot version. I did keep a wary eye out for the creatures, seeing a caterpillar in every fallen catkin.

I had been expecting tricky mud paths when I was imagining today’s walk, but this was fast walking: a gravel logging track, wide and smooth, lined with huge felled oak trunks. Some of them were ancient.

And all were covered in arcane numbers and codes in neon spray paint. The biggest ones even had QR codes on them. There was nobody working today, although clearly massive logging operations had been going on. The woodpeckers were the ones working the timber today, drumming being a constant accompaniment as I climbed.

The gravel road undulated up and down over the forest massif. Sometimes at a crossroads it opened out into cowslip rides, reminding me that it was in France that I had first seen cowslips as a 14-year-old on a French exchange. There was just such a ride in the wild grounds of the family’s country house. I remember being stunned at the sight, and somehow recognised cowslips, even though in Britain in the 1970s and 80s they fell into rapid decline because of changing agricultural practices. So I had grown up without seeing any at all.

The open space and light had allowed some other early wildflowers to flourish in the verges. Here in the forest, they were nearly all various shades of yellow and green: tiny flowering sedges, more crosswort and cowslips, and two or three types of euphorbia.

I took a short detour off the path to have a look at the reforesting operations that were part and parcel of the good management of the forest. On this cool comfortable day, I thought of the smallholder farmers sweltering on their Amazon land as they race to get all their saplings planted before the rainy season is over. I hear it has been a huge success this year. How much easier it would be if they could benefit from mechanised planting, as European Foresters are able to do.

My path turned off the logging track through the woods and became a narrower, more informal path. Sometimes it was asphalt, sometimes embedded scalpings, sometimes cobbles, contributed a timeless feel to this path. Sometimes, best of all because soft underfoot, softly decomposing leaves.

I was admiring the thick ropes of the wild clematis, the old man’s beard, and thinking that even after so many days I was still on limestone, when I suddenly noticed some of the enormous mossy boulders seem to be made of hundreds of thousands of compressed lentil-like shells.

They had fallen from a small cliff face of the same type of calcareous rock — the St Gobain forest has sandstone, clays and limestone layers and beds, through which layers I had been climbing up through.

I couldn’t figure out what they were. They looked like bivalves, but I couldn’t see where the shell would have closed, and they were featureless, more like lentils than shells.

The guidebook recommends a climb and descent up through the woods on a minor path as opposed to an exit from the forest to the ‘missable’ village of St Nicolas au Bois, almost entirely destroyed in World War II and rebuilt afterwards. I was definitely up for a climb, feeling my calves stretch out and glutes come to play. They had been walking flat for so long that the sweaty climb up onto the top of Mont Lorette seemed like another world.

This was familiar beechwood. I was enveloped by what Keats would rapturously have called ‘beechen green’: the softest, earliest downy edible leaves from which you can make a good spring salad.

I could almost be back in the Malvern Hills, were it not for the little VF signs posted every so often on trees, and the little lentil-shaped fossils scattered amongst the beach leaves underfoot.

Because the shortcut climbed so high, we occasionally had views out over the wooded slopes on the other side of the folded valleys. Oh! I have just noticed I said ‘we’. How extraordinary!I walked on, trying to decide whether I was talking to you, Reader, to Stephen, or to the spirit of the forest. At any rate, I did not feel remotely alone.

I joined a D-road next to the ruins of a 15th century monastery hidden tantalisingly behind scrubby woodland for a long climb up a hill so steep it had switchbacks built into it.

More new flowers on the verges for me: here, oxlips, recognisable by the leaves that narrow to a point where they join the base of the plant, and delicate, more primrosey flowers. Very different, I could now see, to the false oxlips which are simply cross-fertilised cowslips x primroses.

I gradually became more aware as I climbed of an insistent sound of chainsaws and finally, near the top of the hill, the headlights of heavy machinery were visible shining through the undergrowth. A lumberjack right on the edge of the road on a bank up above me was cutting through the base of a hugely tall oak tree. I could see the top shaking as the blade bit through the trunk, and tried to increase my uphill pace so I would not risk it falling on me (although I trusted to his expertise not to drop the tree on the road).

As I rounded the corner behind them on the last of the road’s switchbacks, there was a titanic prolonged ripping and tearing sound, and a phenomenal crash as the huge tree came down, unseen behind me in the forest.

Here were the forest operations in full force. A sea of logs lay all around me on the path,

and out on the road giant stacks were being readied for transport.

Although it wasn’t quite lunchtime, I was feeling the need to take the weight off my feet. I stopped at a little forest house called Croix de Sergeant to park myself on a friendly, mossy lump of concrete and rest a little bit, and then set off on the last leg before a little village where I hoped to find a place to sit to have a proper break and lunch.

I regretted at this point not bringing my binoculars, because to add to the liquid calling of the song thrush and the near-constant aggressive back-and-forth of the wrens, there was also a firecrest up in the tallest trees, and somewhere, a crossbill.

I walked smartly to warm up after my break, but kept scanning the verges for anything interesting. The wood anemones were going over now, their flowers drooping, an end perhaps exacerbated by yesterday‘s rain which had made rivulets of the dead leaves on the path, sweeping them away to reveal the sandy substrate, pock-marked with rain. I was surprised not to have seen many carpets of bluebells yet. Here the blue that caught my eye were the spires of Ajuga reptans, next to the taller spires of yellow Archangel.

As I came to the end of my audiobook I heard a bird I didn’t recognise, which Merlin identified as a black woodpecker, a very large species which we don’t get in the UK but which here apparently are not uncommon, especially in mature woodlands such as this 8,470-hectare expanse. It is jet black with a red patch on the top of its head, and wide white eyes. One flew overhead, calling loudly.

Eventually, my forest idyll came to an end and I dropped down to a farm truck that took me into the village of Cassiers-Suzy. The line from ‘Telegraph Road’ came to me — ‘A long time ago came a man on a track/ walking thirty miles with a pack on his back’, and I thought how for centuries travellers (including many pilgrims) would have appeared out of the forest and walked down this same track towards this village.

They would have passed the same ancient farm — where the sounds coming from the cattle shed sounded like a herd of brontosaurus calling to each other. Rather than going into town searching foot a bench, I sat on a handy tyre in the farmyard to eat my lunch. Mindful of the long day yesterday and its effect on my feet, I took my shoes and socks off and let my feet cool in the air. I ate the absolutely delicious second half of the lentil and sausage stew I had made last night.

I had my phone out to take a photo of the old farm courtyard as I passed, when a filthy spaniel came racing towards me, barking and growling, and was swiftly called back by the farmer. He apologised, but I said not to worry — it was her job to defend the farm. After that I was a bit embarrassed to take a touristic photo of his home, so I walked on. You will just have to imagine it: huge pale sandstone blocks creating a courtyard on three sides with house, stables and barns, sitting naturally in the landscape.

The last house in the village had a big wooden balcony at the front and an enormous wooden sign over the top saying ‘Desire’. There was a chap in the garden cutting the grass with a pair of scissors. That would not be my desire at all! I didn’t take a photograph of him either.

I did however, take a photograph of a market gardener digging up a row of carrots and slinging them in a box. They were huge. Long and straight. I bravely engaged him in conversation in French about carroticulture. The soil here was sandy, wasn’t it? I commented. ‘Good for carrots.’ ‘Yes,’ he agreed laconically. ‘Not much good for anything else, though.’

Indeed, the path was all sand here. I climbed back into the woods for the next section and every now and then as the cloud started to lift in the afternoon, I caught a flickering glimpse of my shadow. It was not only the path that was strange, but also the woods. One section had a whole row of lilac trees just behind the brambles that formed the wood’s edge,

and badgers had built a vast sett among the lilac roots.

Three lads were doing something to one of the trees. they wished me a cheery good day as I passed, then they attempted to call their dog to them. Darko, of whom I simply saw slightly folded over ears and a muscular appearance, paid not the blindest bit of notice to the recall, and came out of the woods to have a go. I didn’t make eye contact with him and just walked on calmly, he did try to bite one of my poles, occasioning more urgent recalls and the involvement of a woman who was further out in the wood. It was one of those useless efforts where every time the dog barked they called its name. Effectively untrained, and not particularly friendly.

The woodland continued to feel strange, with a variety of flowering tree I didn’t recognise, and stands of tall straight trees with an unfamiliar bark, that were either dying or dead. It was a similar story with oak after oak. And the wood was full of cuckoos calling. Further on in the strange woodland garden, a tiny white car was driving along the track, very unexpected in this wild place. And it was another lad, and his girlfriend with a Chihuahua on her lap. Darko will make short work of that.

I felt it was a momentous occasion when I came across the first grapevine I have seen since arriving in France. It feels like a little preview or foreshadowing of the future, when I will walk through the champagne region (yes, reader, this is the reward for every traveller walking to Rome in the footsteps of Bishop Sigeric). It was a little step-over hedge made entirely vines running all the way round a house. Neatly pruned and just coming into bud.

The path turned off before getting into the village proper to become a grassy country path up which a beautiful black horse was being ridden. I asked the lady what breed it was and she said it was a Frisian, a type of light draft horse, which you could see from its size.

There was evidence that an awful lot of countryside work was going on around here. A long line of trees had been mostly felled on either side of the path, the timber removed and the brash neatly stacked to create a dead hedge.

There is so much of France, and so many people working the land. The woods that I have been walking through today have all in someway been worked — I should say, tended. It was only the very strange wood that felt awkward and wrong. Every other step of this path today has been absolutely lovely.

I had another little sit down at a farmhouse that is photographed in the guidebook, with a note to the effect that you can tell it’s very old because it has a defensive wall and a tower. This felt very familiar to me from the (mostly Norman, come to think of it) farmhouses in the Welsh Marches.

Here, the house proper was hidden from the road, which was a real shame as it looked stunning from what I could see above the gate. I startled a green woodpecker from the lawn in front of a grain barn which had buttressed sides like a chapel.

From this farmhouse, the first glimpse of Laon ok its hilltop vantage point rises from the fields. It looked so close, but when I put the distance into Google Maps, it says that it was still 4 km away, a 55-minute walk. I found this hard to believe and rather depressing, but I slogged on.

Google Maps had suggested a more direct route to the old town than the one proposed by the Via, so I decided that rather then looping round to go via the lower city and the train station I would scale the cliff face. There was a path on the map that did just that — and at the bottom of the climb a sign confirmed my choice.

Well — easy it wasn’t. But it also it wasn’t daunting: I told myself ‘you have been trained on the Bromyard Downs and the Malvern Hills, on the South West Coast a the Devil’s Staircase in Glencoe. This is achievable.’

And of course it was, 110m of climb, though admittedly an extremely steep seven minutes. I was glad for all the calf stretching in the Bois de Saint—Gobain.

At the top the city walls ran in a ring around the old citadel, huge chunky quarried boulders, am additional protection from the medieval enemies who had just exhausted themselves hailing themselves up to that point.

I decided that I would go and visit the cathedral before going to the hotel, as once I reached my room I wouldn’t want to get up off the bed.

The old streets were so reminiscent of Siena, another medieval city on the Francigena, far ro the south: curving and short-cutting, narrow streets with ancient buildings on either side, here a decidedly French character instead of Italian. Cobbled streets and interesting shops, and even (something I had not seen this far in France, to my disbelief) a café culture.

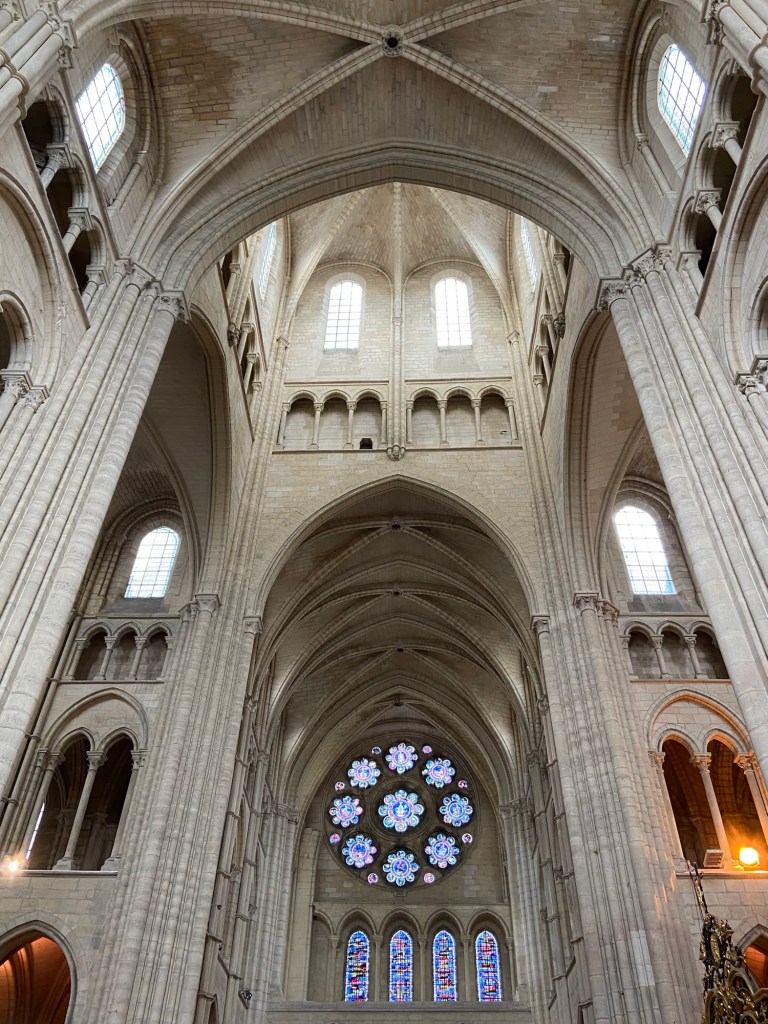

The cathedral of Notre Dame when I saw it through an alleyway made me gasp.

It was huge — incredible — ancient; decorated all over with gargoyles, carved arches and pillars stacked upwards to the heavens.

It was extraordinarily impactful, and the connection right back to the Gothic cathedral of Canterbury suddenly struck me — that I had walked all this way, on foot, with my rucksack and my poles.

Inside the connection was even stronger, the rectilinear structures of the exterior supporting pale soaring arches and vaults.

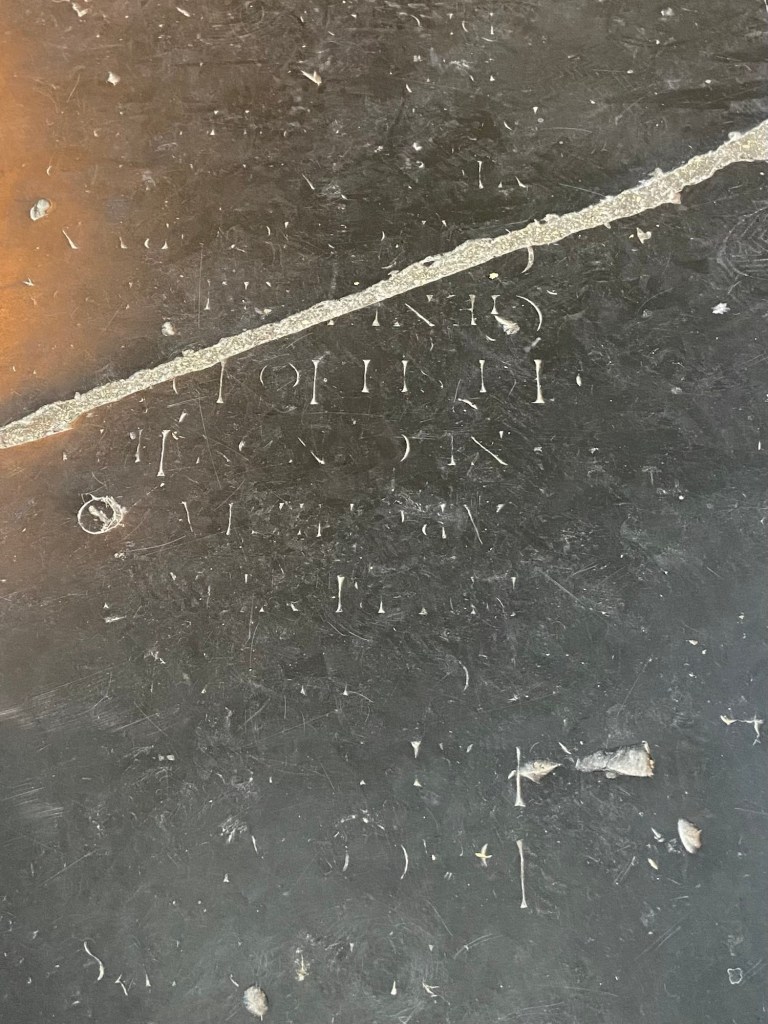

Under my feet were impossibly ancient tombstone slabs, inscriptions and carvings worn away to illegibility over nine centuries.

The impression of length and height was increased by regression

And vertical narratives of jewel-like stained glass rose in square panels

which served to draw the eye to the central rose.

After so many days under open skies in the vasty fields of northern France, in the landscapes where twentieth-century famine, sword and fire had crouched over trenches of mud and blood and where the dogs of war had laid waste to entire towns and villages, that this jewel of the medieval yearning for meaning and purpose had perfectly survived, seemed like a miracle in itself.

Stats for the Day

Distance: 27.81, lengthened by two kilometres wandering the old city

Time: 6 hrs 18, plus two hours of longer or shorter periods of rest.

Pace: average 4.4. Hilly today

Today’s Harry Potter moment

Another long but interesting day. The cathedral is stunning and I imagine precarious wooden scaffolding, with brave builders accurately placing stone upon stone. I wonder if they ever imagined that the fruit of their labour would have survived so many centuries. I hope you have a more restful day today. xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes — it made me think of that ruined Abbey that we saw way back on the day we left Ablain Saint-Nazaire. They were just the towers left, and I couldn’t imagine how the workers would’ve got up there, or what it would’ve looked like originally. Something very like this, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have two more long days and then a silly short one and a blessed day and a half in Reims for Easter.

LikeLike

That cathedral! And to imagine the awe it would have provoked in an earlier pilgrim, given the effect it had on you? What a triumphant end to the day. Also, new fact, I didn’t know one can eat young beech leaves. My salads will be thus adorned from now on! Keep up the foot care….. xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love you, Jane xxxx

LikeLike

How impressive, this cathedral, after so many days of countryside walking…!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes — I am looking forward to Reims

LikeLike

One of the perks of being married to Arthur is staying in terrifyingly bad hotels selected for their proximity to amazingly beautiful cathedrals. I remember Laon as glorious and I’m so glad you enjoyed it after your long day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bet we stayed in the same Laon hotel! Airbnb tomorrow in Reims. Luxe.

LikeLike