Emile Zola, Germinal

Who could say that the workers had had their reasonable share in the extraordinary increase of wealth and comfort during the last hundred years? They had made fun of them by declaring them free. Yes, free to starve, a freedom of which they fully availed themselves. It put no bread into your cupboard to go and vote for fine fellows who went away and enjoyed themselves, thinking no more of the wretched voters than of their old boots.

We slept extremely well last night in this beautiful farmhouse after our day out in the sun, and woke to a lovely farmhouse breakfast courtesy of Colette.

The young pigeons she said were being let out to train, flying around the courtyard to imprint the location so they would always know where to return.

We took a photo for her extensive records, although sadly we cannot lay claim to being anything like as interesting as those features in the Hall of Fame photos in the kitchen: oldest pilgrim (83 years old), youngest pilgrim (9 months, being carried by her mother), fastest pilgrim (the then-world record holder for the half marathon), first pilgrim from Uruguay, and so on.

There had been a sharp frost overnight and everything was rimed with ice. We had an extra layer on and strode straight up the hill to warm up our fingers.

The church was already in sun, and we went in: the church was dedicated to local son St Benoît Labre, patron saint of beggars and the homeless, who himself became a homeless mendicant of the Tertiary Order of St Frances after he has been refused by the Trappists, Cistercians and Carthusians. He died of malnutrition aged 35 in Rome. A sad story, but the church was full of light.

We started the walking day talking about Trump and Musk and the effects of tariffs — something about which I technically know little but about which Stephen who is an actual economics expert knows an awful lot. This was absolutely not the kind of conversation topic he wanted to follow and in short order he was cross and frustrated (not with me!) and we decided to switch subjects.

Organic potatoes! There were weeds growing between the furrows in one field. Stephen said it didn’t matter because the potato haulms (in fact he didn’t say that because he didn’t know the word — but it’s the leafy part, anyway) cast such shade that they outcompete the weeds; this was different to orchards, he went on to say, where you want close-mown grass between the rows and weedkiller around the base of the trees to eliminate the flowering weeds. This is because fruit blossom is very low in nectar and pollen quality, and so bees would prefer to visit, for example, dandelions, and you want to make them visit the tree blossom. ‘But that means,’ I said, ‘you are forcing the bees to work twice as hard to get the energy they need from the work they do.’ ‘Yes’, said my apiarist expert. And I was unhappy about that.

We were traversing a post-industrial landscape today, our route connecting a number of small mining towns with the terrils dotted about between them. The towns and villages were were no longer of a visibly agricultural character but clearly industrial, with identical rows of 19th century workers’ housing in very much the same vein as the ones we are familiar with from south Wales and West Yorkshire.

The towns had grown into one another as one more or less continuous urban sprawl, and as we entered Lozinghem we passed two men in a garden where they’d clearly been working since the early hours pruning huge boughs off their trees. The older man, white-haired, was sitting in his wheelbarrow, exhausted. ‘Boucoup de travail!’ I called, and they agreed it was time for lunch. We stopped too: by the war memorial with its slightly tattered tricolore. We watched a pair of bobbing wagtails on the grass and swallows and martins flying around the church tower, and a man not picking up after his dog.

Later on we saw a sign perfectly directed at him:

As we came into the town of Marles-les-Mines we passed a number of connected schools and colleges all named after the great 19th century novelist, poet and journalist, Émile Zola.

I had read Zola’s great novel Germinal at university and been very affected by it: the story, set in this region, of grinding poverty in a mining community and a consequent miners’ strike in the 1860s. ‘Germinal’ is one of the spring months in the French Republican Calendar, corresponding to March 21 — April 19, so the time of germination and budding we find ourselves in now. The revolutionary calendar was intended to be secular and avoid Christian reference points so took as its starting September 22, 1792 (1 Véndemiaire, year 1), the date France has been declared a republic.

We wondered what lessons the students at the schools took from the works of Zola — but it would have been almost impossible to have known because there was a mysterious absence of youth around the place.

In fact, around pretty much everywhere. The schools were closed, so they must be on holiday. But where were all the teenagers hanging around on street corners? Where were all the kids?

We saw one solitary lot in a country park in the centre of the mining town which had been created to follow to follow the river Clarence as it snaked its way down the valley. They were doing some sort of holiday club or youth club organised frisbee game.

It was lovely to get off the pavement which has been our constant companion almost the whole day. The park was cool and green and the river was full of brown trout.

The park ended at a factory making car bumpers, all stacked up in crates, perhaps ready to face the storm of tariffs

But our route took us down the side of the industrial area, a grassy path with bird cherries and the green water alongside.

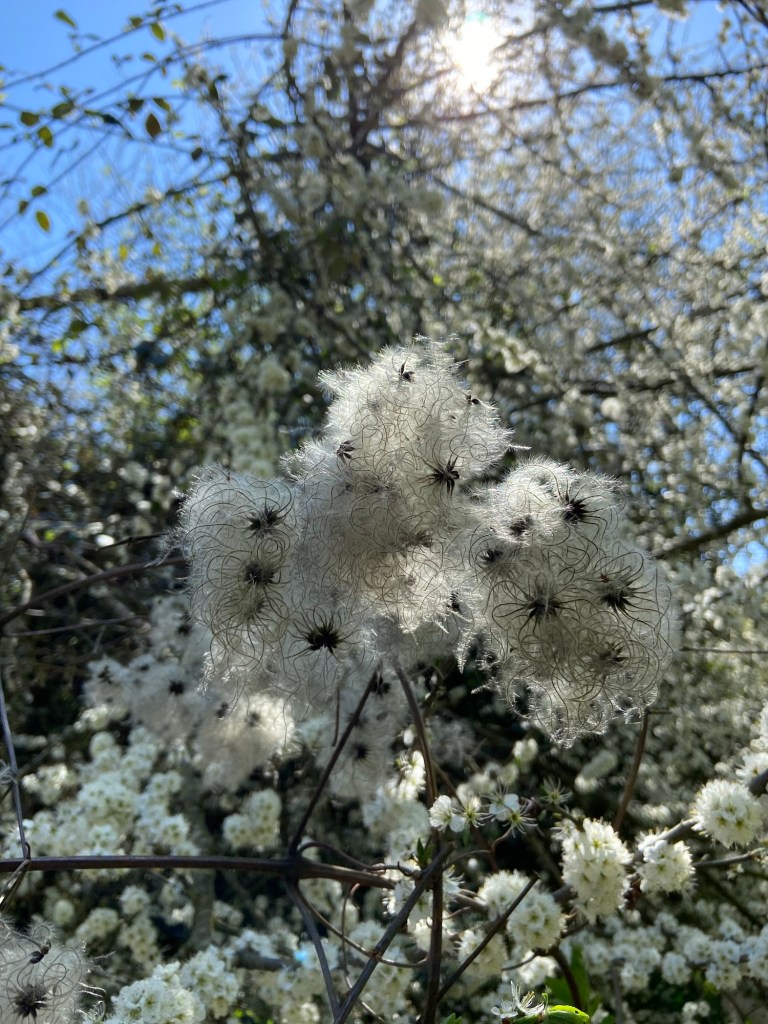

Here, last year’s old man’s beard held its own against the fresh white of blackthorn blossom,

And at the very end of the park a leisure lake had been created, its shores populated by trout fishermen, and in the centre a single grebe diving periodically for nesting material.

The town had been almost entirely populated by Polish miners in the 70s and on our toil uphill near the end of the day we passed a memorial to the six Polish townspeople who had died in an explosion at slag heap no. 6 in 1975.

But it wasn’t the first tragedy to befall the workers at this particular mine: in 1939 a German bombing raid has caused a dust explosion in the mine this terril was associated with, killing 34 miners.

Further up the hill there was a Polish bakery proudly announcing they were the third generation of the same family to bake bread there.

Four more young teenagers passed us, like a mining town version of the Famous Five, walking the family dogs down to the park in the shadow of the vast terril that loomed over the town.

At the top of the hill was the last of the green corridors of the day, connecting Marle-les Mines to Bruay-la-Buissière, passing quite close by a gigantic terril on one side

and on the other, appallingly, vast stands of last year’s Japanese Knotweed stems. This year’s new growth was pushing inexorably up from the ground, vigorous and inevitable.

On this day of powerful spring sun, of the buds and the blossoms and the energy, their chilling upspringing reminded me of the last metaphorical image of Germinal:

Now the April sun, in the open sky, was shining in his glory, and warming the pregnant earth. From its fertile flanks life was leaping out, buds were bursting into green leaves, and the fields were quivering with the growth of the grass. On every side seeds were swelling, stretching out, cracking the plain, filled by the need of heat and light. An overflow of sap was mixed with whispering voices, the sound of the germs expanding in a great kiss. […] In the fiery rays of the sun on this youthful morning […] Men were springing forth, a black avenging army, germinating slowly in the furrows, growing towards the harvests of the next century, and their germination would soon crack the earth asunder.

It’s supposed to be a positive note to end the book with but I couldn’t help, on this day which started with the world being a little too much with us (to paraphrase William Wordsworth), thinking also about the endless painful cycles and revolutions.

But my final thought of the day was shaped by our arrival at the kindest of pilgrim hosts, to be greeted by the sign at her door:

If people can love each other just a little bit, they can be so happy

Émile Zola, Germinal

Stats for the Day

Distance: 21.56km

Climb: 286m

Time: 4 hrs 47 mins

So much in this today! I love your conversations, and to be walking in Zola’s manor too. It is quite the journey, isn’t it? Xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! And every day is different

LikeLike

Can’t tell you how much I am going to miss the conversations

LikeLike

The conversations make me chuckle, I can hear you! I’m not happy about the bees either, they have SO much work to do! Loving the blog, literally smelling the pastries and coffee xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love you, Susie xxx

LikeLike