Through the interstices of things ajar

Robert Frost, ‘On a bird singing in its sleep’

If there is anything that impressed me yesterday it was the expansive views over the river Severn, not just up- and downriver, but also across it. In the time it took me to walk from Sharpness to Aust Cliff yesterday, the tide went from almost high to rounding the turn and coming in again, which gave me the opportunity to appreciate the enormous sandbanks and shoals of Lydney, Sheperdine and Oldbury, accentuating my sense of the breadth of the river. The Romans had build Gloucester precisely to control the crossing of the Severn into Wales, at the time the furthest point downstream where it was technologically possible to construct a bridge. Then, they used the natural division of the river into its East and West Channels around Alney Island to achieve the crossing in two stages. Telford had been asked to consider a crossing but nothing had come of the project, and it was not until the ill-fated railway bridge was put up in 1876 at Sharpness (that ‘Ness’ narrowing the river’s width and making it the most sensible place to span the river) that a crossing was established further downriver than Gloucester. The existing seagull-like grade 1-listed Severn suspension bridge opened the year before I was born, in 1966.

The Severn Bridge was always an iconic moment of our monstrously long 7-hour holiday journey in the 1970s going from Kent to the tiny hamlet of Llaneglwys north of Brecon, where my parents had a little house. I remember being awed every time passing under its towers, and stopping at the Aust service station just beforehand and the ritual of paying the bridge toll only increased the anticipation. Stephen and I crossed on foot last August, all 1.6km of it, on one of our pick-up days filling in the little sections of the Lands End to John O’Groats route.

It was none the less exciting for taking it slower — more so, even.

And I hadn’t realised before crossing it on foot that the architects had taken a leaf out of the Roman playbook, and used the bulbous spit of land where the river Wye debouches into the Severn as a springboard for the easternmost section of the bridge.

For that matter, I hadn’t even realised, crossing the bridge as a child, that the Severn Bridge spanned both Severn, and the Wye rivers.

Today I stayed on the eastern bank, I did not cross the bridge. When Stephen and I walked this section of the embankment in the other direction last year the upgraded flood defences had still been under construction, and the footpath was closed. To get round the edge of a pill at low tide when the entrance to the embankment was closed off with what a workman told me today were called Harris barriers, we had practically had to hang to them by our fingernails. In the middle section of the path we had had to untie and then re-tie some more, and at the end, the same to get out onto the road.

So my heart sank at the sight of the Road Closed sign and construction workers at the gate. There was no other alternative than a long slog out to the A-road followed by a long slog along it. However, I could see a dog walker ahead of me on the embankment and there was another one coming along behind me — so in my mind we were an inexorable convoy.

I moved onto the path past the vans, and the men in their hard hats and ear defenders. “Morning!“ one called out, volunteering that they were actually from the environment agency and they were clearing the ditches of silt from the last high tide. They wouldn’t have to do it again until the next one in August. They come back to strim and re-seed and do other maintenance jobs. Totally innocuous! I could proceed.

It wasn’t a very nice path, in fact a lot less nice than it had been last year when it was ‘grassy and wanted wear’, made up with hard-packed rocks and scalpings. However it was only 3 km to the other end, and the views of both bridges were spectacular, and as I picked my way on top of the winding ribbon of sea wall between the river on one hand and the farmland on the other, I mused that given this was one of the first four short sections to open of the newly-designated King Charles III Way (déja the English Coast Path), it was a pity that a) the path didn’t feel less like a road, and b) the front dog in our stately convoy wasn’t a King Charles spaniel rather than some kind of cocker.

There were some mucky pond affairs behind the embankment two thirds of the way down the path, and what looked like an embryonic visitor centre. The effect was that the building site had just draped itself all over the little lakes. But there were some ASBO reed warblers disturbing the peace inside one patch of reeds, and the shadowy white shape of a swan nesting deep within another. As well as the coots and ducks and the swallows catching insects newly-hatched from the surface of the water, there was a tufted duck doing slow circles while another showed off next to her. The wildlife existing in the middle space between natural and built environments.

The footpath that I had originally planned to take off the coastal path did not seem to exist anymore, but that didn’t matter because I wanted to walk into Severn Beach in any case; in the first place, to revisit the second Severn Crossing: the monumental 5km-long Prince of Wales Bridge.

My parents moved to Wales in the mid 1980s, and so our holiday visits predated the Second Severn Crossing. After my final short stretch on the sea wall again to begin with today, this was where I was due to leave the river for the final time as it loses itself in its estuary, turn inland and head for Bristol, finishing my day in Westbury-on-Trym and leaving an excitingly few kilometres to go tomorrow to get to the lunchtime concert.

Only thirty years after the Severn Bridge opened, the weight of traffic had increased so much that a relief bridge was rendered necessary. The bridge was to be built right at that point where tidal river became tidal estuary, and at the time of construction there were passionate environmental concerns voiced about the effect on the flora and fauna from the disturbance of the habitats consequent upon the construction. The birdlife seemed to manage, but the eelgrass beds underwater never fully recovered from the increase in water turbidity from the building works. The Second Severn Crossing opened in 1996, the consortium that built the second bridge taking over the £100m debt from the first and being given a 30-year concession to manage them, and collect tolls from both, to recoup some of the construction costs.

The approach along what used to be the shore was itself monumental: great chunks of rock stabilise the tidal margin, and over the decades have become covered in a vivid yellow lichen.

Unknown hands had set driftwood branches into the rocks like disturbing ritual poles.

The bridge curved away 5km into the distance, massive piers and stanchions close to, and seeming airier the further it stretched away, a thread of concrete and metal arcing over the water and connecting England with Wales.

On the other side of the bridge it was the same, but instead of the river the Severn Estuary opened out into the sea, with Portishead and Avonmouth ahead of me.

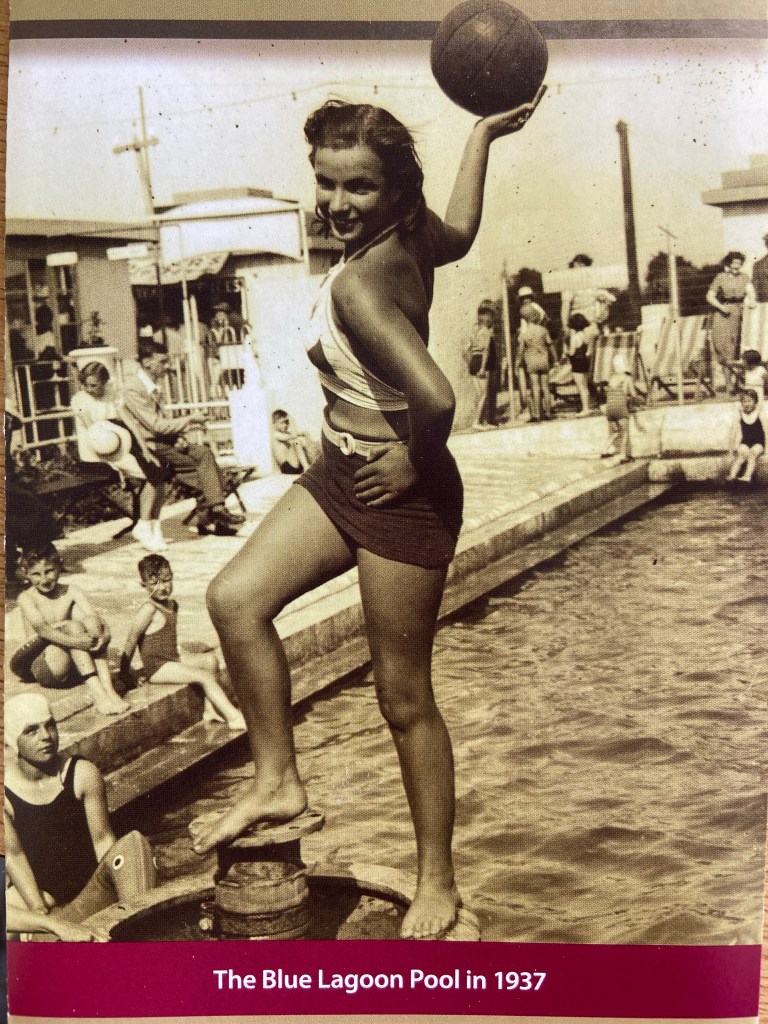

The other reason to visit Severn Beach was Shirley’s café. It’s is a shrine to the history of Severn Beach, which in the 1930s was a thriving resort connected to Bristol by a railway that allowed families to access the coast. The Blue Lagoon was an enormous cold-water lido which according to the heritage trail leaflet in the café had ‘changing rooms, diving boards, fountains, a waterslide and children’s seesaws in the shallow end’, and Water Carnivals held there included ‘Bathing Beauty competitions, Personality Girls [whatever they were], and Seaside Revues with dance competitions.’

The resort is long gone, and all that remains of the pool are the ornaments at the base of the steps leading up to the pool, with their traces of blue paint.

The path that I eventually stitched together was a strange bridleway (complete with recent hoofprints) that must have existed as a right of way long before the Western Distribution Centre, a series of enormous straight roads, roundabouts, and vast warehouses, came into existence.

Drainage ditches (here called ‘rhines’, pronounced ‘reens’) run alongside and at right angles to each road, and crossing one I disturbed a little family of moorhens, the tiny fluffy chicks making for the cover of reeds in alarm. They seem to be scratching a living in between the enormous amount of plastic rubbish that has just been thrown into the ditches and forgotten about.

Búran waved at me from his burger van, the Filling Station. When he heard what I was doing, he shook my hand in his great meaty paw, and boomed, in capital letters, YOU MAKE LIFE! He gave me a free bottle of water, and showed me photographs on his phone of the most beautiful parts of his homeland of Turkey he could think of, to underline his point.

Búran gestured up the road the way I was heading, and said it was all closed along there. ‘There is a footpath’, I told him. ‘Have you checked?’ he asked, doubtfully. ‘Yes!’ I said, enthusiastically. But I wasn’t confident at all. They were just breaking ground on a new development of houses, simply enormous, and looking on from the end of the road by a colossal Tesco’s warehouse, I wasn’t at all sure that the footpath had not been obliterated by the building work.

When I got down to it, though, I saw a pedestrian route or sorts had been signposted around the Harris barriers and I picked my way through the distressing amounts of garbage thrown out of truck cabs, including plastic bags containing driver dumps, and large bottles full of urine.

I was mighty relieved to see that the path did still exist, so I followed the thread of green between enormous flat expanses of hard-core to either side. Some tiny fish were flicking about in one of the drainage ditches, and a stonechat flew ahead of me, stopping on the posts and tops of the new fence posts. There was a dreadful sense of life being eked out in this pitiful thin remnant of natural landscape. Worst — or best — of all an anxious squeaking started up from the waste ground to my left, and a lapwing flew up into the air, joined by another two. I wondered whether they might be groundnesting, and be panicked by my passing by. I felt desperately sorry for them, trying to nest on this wasteground that once had been fields. They are condemned.

The path exited onto a cycle route that made for faster going, although it was harder underfoot. I came across Alan from the Isle of Man, resting on his grand cycle trip the full length of the mainland from Lands End to John O’Groats, and I took the opportunity to rest myself and chat awhile. Today he is heading up to the Severn Bridge whence I had come, and from there to the Forest of Dean on the other side.

The relative of bulk of Spaniorum Hill now lay in front of me.

To get to it I had to cross yet another field of cows — my last! Some of them would definitely have liked to have had a go, but were mercifully prevented by an electric fence. They kept pace with me on the other side, though, but were ultimately stymied in their evil intentions.

As soon as I climbed the style onto Spaniorum HillI started to feel the odd tension that had been with me since this morning drain away.

By the time I got to the top and found myself in one of the 400-yr-old ancient bluebell woods which cover 40% of Spaniorum Hill, the process was complete.

The path took me past the ultra–swanky Berwick Lodge Hotel, where I certainly did not belong today,

and after a bit of faffing about, making mistakes with the route, I crept along the margins of its drive, and just outside the entrance found some large chunks of rock on which I could sit for 15 minutes, let my feet recover, and my battery charge a little bit — both my actual battery and my energy levels. I even felt warm and fuzzy about the cows’s head next to me, and enjoyed sitting under the cherry blossom trees eating half of a coronation chicken picnic roll that I’d bought from a bakery in Severn Beach that had been recommended to me by Jennifer from my Airbnb last night.

The ridge of Spaniorum Hill forms part of a 45-mile named route around Bristol, the Community Forest Path which links up green spaces all around the outskirts and edge of the city. My route was to take me as far as possible along this path through the urban landscape. The hill is also part of the Spaniorum Skyway route, the work of local charity A Forgotten Landscape, whose Facebook page speaks to the many active projects and the great amount of outreach work they are doing in the Lower Seven Vales to ‘conserve, enhance, explore and restore’ the heritage of the area.

And so my final approach into the heart of Greater Bristol threaded me through precious green spaces, remnants of bluebell woods up against new housing developments,

Buttercup meadows with horses grazing alongside the railway line, and woodland backing on to residential towers.

The path took me through the middle of Henbury through a wood thickly carpeted with cow parsley, bluebells, and wild garlic, fallen trees left to provide habitats for beetles and other invertebrates, food for the birds that sang in the trees above my head. Two DofE groups of younger teenagers with their endearing characteristically enormous and badly packed rucksacks with extra gear strapped to the outsides were on their way to discovering the great outdoors.

On the map the whole of the path from Severn Beach pace the Spaniorum Hill section had looked as though it was urban. Paved it was, but there were often grass margins or soft dried mud and leaves at the sides of the tarmac to walk on, and the green nature of the Community Forest Path had an undoubted effect. As some graffiti on the rear of a shed by the side of a school sports pitch backing onto the green cycleway put it: things can only get better.

Buoyed by this positive sentiment I climbed the second to last hill (the last led up to my Airbnb, of course), and descended into Westbury-on-Trym next to a solid stone wall, pausing to admire the ivy-leaved toadflax and then noticing it was a daytime refuge for a pair of stripy snails.

Westbury has the atmosphere of a little village with an interesting history, lost in time.

I’d planned on getting supper from a supermarket that I could eat in my Airbnb, some salad and fruit for sure, yoghurt and a quiche, or similar. But the Seven Eleven was a wasteland.

Lucky I had conserved the second half of my chicken sandwich!

Sheila’s Airbnb when I got there (waking her baby granddaughter with the doorbell 😱) was what could only be described as a haven, with a tiny, beautifully-equipped kitchenette, a comfy chair and kitchen table, and a glorious bed. I’d arrived just before 3pm, so there was plenty of time to rest and relax and patch up my feet, and most miraculous of all, Sheila offered to DO MY LAUNDRY! A total saint!

Stats for the day

Distance: 18.48km

Fruit and Veg Supper Options in the Westbury-on-Trym 7/11: cabbages — 2, onions — 1, lemons — a net bagful

YOU MAKE LIFE! You personality girl. Xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

😆😆😆😆😆

LikeLike

I hope you’ve got a decent breakfast sorted?!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Breakfast in bed, no less!

LikeLike

I loved reading this. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh thank you!

LikeLike