What we face may look insurmountable. But I learned something from all those years of training and competing. I learned something from all those sets and reps when I didn’t think I could lift another ounce of weight. What I learned is that we are always stronger than we know.

Arnold Schwarzenegger

It was with a huge pang of regret that I packed up in my luxurious AirBnB and set off into Cosgrove on the very last section of the Grand Union Canal. My impression was that it was quite an upmarket place, and this impression was confirmed by the stately bridge over the canal on the edge of the village.

Here, cows came right down to the river to drink, even standing in the water, looking like a scene from centuries ago.

My job, however, was not to moon over the bucolic, but to source some food. I could see on the map that there was going to be no chance of finding either lunch, nor supper, and therefore neither breakfast for tomorrow morning. Quizzing the canal folk revealed that the holiday park next to the canal had a food shop in it.

As a shop, it was excellently stocked. My problem, though, was that it mainly sold ingredients or nutritionless snacks, rather than the kind of food that I might be able to eat for lunch, supper and breakfast without cooking it. Fuelling my walk has been a constant concern, and there have been times when I have not got it right — with consequences. Carrying three meals–worth of food has a weight implication, though.

In the end, I chose hummus, some crisps, two pork pies, a bell pepper and an apple, and for breakfast, a yoghurt pot with granola, and some blueberries to add. This all looked like pretty sensible walking food, but it weighed about a kilo and a half in total. I have discovered over the past few walks that there is a sweet spot in terms of weight: 9.5 kg is pretty much my limit if I don’t want to be really uncomfortable, but here I was with probably about 11 kg to carry. There was nothing for it though. I shouldered what already felt like an unmanageably heavy pack, and set off again.

At the end of this short section of canal the land fell away and the canal kept going: upon the famous Cosgrove aqueduct. The end had come upon me so suddenly — it was a strange sensation climbing down the steps that led to the river Great Ouse that was to be my companion pretty much to the end of this walk.

The river was immediately lovely. In fact, I was so enchanted that I forgot to turn around to have a look at the aqueduct, and as a result I have no idea what it looked like. Which is a shame as the Grand Junction Canal company had tried and failed three times before the successful bridging of the Great Ouse in 1811 with this ‘Iron Trunk’ aqueduct, the oldest broad canal iron trough aqueduct in the world.

As the river twisted and turned, the water flowed faster or slower, and banks of reeds of various kinds helped slow the water and provide a habitat for the very many dragonflies that were visible.

On the other side of the river was a campsite, and the whole bank was lined with tents and people quietly enjoying the water.

Many were fishing.

On the side where I walked there were nature reserves stretching out to the side, large tracts of fenced-off land, encompassing scrub, small lakes and huge reedbeds. At the point I joined the Ouse, it flowed on the edge of a country park, one of a huge number of wetland habitats joining up all along the valley of the River Great Ouse here. There are lakes and channels and such a confusing number of waterways, that it is clear to see how the river running over flat land can create a fen. Here many of the lakes are restored gravel pits, but many of the channels are not the result of flooding, but are in fact controls for flooding: without the division of water into multiple channels, every time there was excess water in the system, the path of the river would move. This would be unsustainable for a land for centuries, so heavily managed for agriculture and habitation.

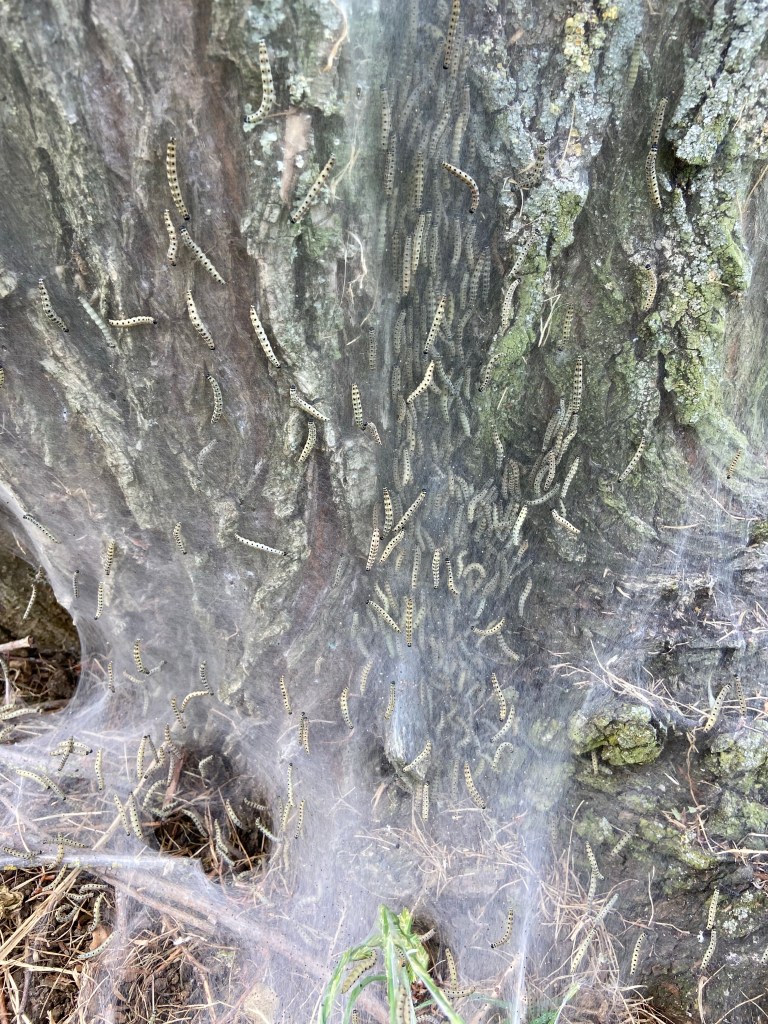

As the river approached Newport Pagnell, the reserves fell away, and the river took on the character, much more of an urban waterway. Lines of white willows punctuated its length, and when I looked carefully, what I thought had been seed fluff turned out to be sheets of the great webs spun by ermine moths that I had seen way back in Herefordshire.

The caterpillars coated the entirety of the trunk, crawling behind their silken screens.

All too soon the Ouse Valley Way left the river and turned into town where, to my great shock, I was back on the Grand Union Canal! I had a lurching sense that I had taken a wrong turn, and was somehow going back on myself, but I checked the map and, sure enough, the Grand Union Canal wound its way through the outskirts of Newport Pagnell. It was very odd: I had accustomed myself, first to the canal when I left the river Avon, becoming constantly aware of the stillness of the canal water, and had joyfully reacquainted myself with moving water and a natural profile at the aqueduct when I picked up the Ouse. But here I was again on the towpath. I felt as though I was rather plodding along. And it was hot and very humid.

This section of the canal was more obviously urban: there were several abandoned electric scooters half buried in the bushes, a good deal more rubbish everywhere, and evidence of some extremely ill-advised open barbecues, which I imagine risked sparking wildfires in the drought we have had.

The path at last turned off the canal and I could focus again on getting to the river – through a meadowland at first, the site of a lost village and a ruined medieval church. It was fiercely hot and my pack was uncomfortably heavy which I found additionally tiring, but I forced myself to eat some lunch — a third of the pot of hummus and some crisps. I was most grateful I think for the salt in the crisps.

And thus sustained, I found myself on the edge of a long-awaited part of the route: the Linford Lakes, managed by the powerfully effective Milton Keynes Parks Trust (who also manage the country park where I was to stay that night, and the reserves all along the banks of the Ouse thus far). Reading up about them the Lakes seemed to be the most wonderful mosaic of habitats for a huge variety of waterfowl. I had had to plan for this in advance and purchase an annual pass, and it was this place over which I felt the keenest regret at having to leave my binoculars at home.

As it turned out, the entrance to the Linford Lakes was miles away. The path that I had traced through the lakes was effectively unreachable, even though the various bodies of water and tantalising hides were invisibly close, on the other side of hedges and screening trees.

Oh well — I shall return with a car and binoculars within the year, and thoroughly enjoy them.

So for the next hour I walked along road edges and paths which on the map seemed to wind alongside systems of lakes but which were in practice simply rat-run corridors alongside housing estates, with the lakes and ponds hidden from view behind thick hedges. My pack seemed to get heavier and heavier.

The sense of urbanisation rose to a peak when I crossed the M1 (a milestone!) and then at last I was back out in the country again, contending mentally with cows in fields and gripping my poles tightly, whereas in reality they turned out to be as enervated as I was.

In this heat, I knew I would need 2.5 litres of water for a day’s walk. But each litre weighs a kilo, and Stephen and I had talked it through and agreed that the best thing to do was to take just over a litre, and to take every opportunity to drink a glass of water as I went, or to buy a small bottle to carry with me to supplement what was in my pack. The trouble was, today I could see that there was going to be nowhere to fill up. Sure enough, by about two in the afternoon I felt that my water must be about to run out. I knocked on the open door of the farmhouse to beg a glass of water.

The woman who answered was an enthusiastic self-proclaimed walking expert who professed to have done all the long distance routes of Britain. She said what I needed was to fill my water bladder. I was too exhausted and overcome to say that I couldn’t carry the extra weight — or that putting the water bladder back in my pack was almost impossible without emptying everything out. She got me the glass of water but insisted that I went over to the farmyard tap and get the bladder out of my pack, and then changer her mind and took it inside herself to fill, looking critically at the water left in my pack and commenting that her guide on the Inca trail would have fined her for having water left at the end of the day. While she was gone I cried into my water glass. Sure enough she came back with two full litres – two heavy kilos – and while I struggled (unsuccessfully, as I had known I would) to put the bladder back inside the pack, she barked out questions about my route and offered nothing but criticism: ‘oh, but you’ve gone the wrong way!’ ‘There’s nothing to see there..’. Why don’t you just go straight from here to Bedford?’ She thought I was a rank amateur.

I thanked her profusely for her kindness and her advice and stumbled on up through her pitiless cornfield carrying the 12.5-kilo pack, and when I had reached the boundary of her land, I took the bladder which was sticking impossibly up out of the top of the pack, drank a third of the water, emptied a third out onto her corn, and put the bladder back into my pack. It was still about 1.5-2kg over my maximum weight, but it was now not physically impossible to carry.

Tyringham was the next village – or hamlet, rather, plus an enormous hall which the map said was a clinic. Perhaps they would take me. I have just looked it up and it closed decades ago, but when open it offered a variety of naturopathic treatments including ‘acupuncture, osteopathy, hydrotherapy, herbal medicine, homeopathy, dietetics, exercise and relaxation’. Yes. I would have been grateful for any of those. The building was designed by Sir John Soane with Lutyens gardens and parkland. I am sure I would have found the whole thing very relaxing.

It started raining. I turned in at the churchyard on the edge of the parkland next to the clinic and sheltered under a tree. I couldn’t go any further if it was going to pour with rain to add to the weight of the pack and my worsening blisters. The chestnut tree had a canopy, and an obliging ivy-covered tree stump underneath it which provided excellent shelter and somewhere to sit. I got my phone out and tried to find some available accommodation in the next few villages. There was nothing. I phoned Stephen to talk things through, but he didn’t pick up. I had reached rock bottom.

So there was nothing for it but just to shoulder my over-burdened pack and carry on. It was only another hour’s walk: surely I could do that — just by putting one in front of the other. I took a road shortcut — perhaps harder on my feet but shortening the distance.

In the event, the rain didn’t materialise. I was on the very edge of the storm which was depositing its monsoon rains to the west of me – although, like the cows lying down, I had been convinced the clouds overhead were going to open.

And then finally there was the last field, the edge of the council-run Emberton Country Park, with the campsite clearly visible beyond the trees.

I was the only one in the field, and so I pitched right next to the toilet block. I got the tent up and ate one of the pork pies (which surely had weighed two kilos on its own) and had a shower, and gradually recovered. I did a lot of just sitting, and allowed myself not to write the blog. I ate more, and read, for comfort, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden instead. It was every bit as effective therapy for body and mind as a week at Tyringham.

Horrid woman! I’m glad you emptied out the excess water! You are a star for trudging on.

LikeLiked by 1 person