Robert A. Heinlein, ‘Stranger in a Strange Land’

‘Is This Paradise?’

‘I can guarantee you that it isn’t,’ Jubal assured him. ‘My taxes are due this week.’

Chalindray is according to local legend the ‘Land of witches’, but Grandchamps was to me far more bewitching. ‘La Vallée Verte’ had sounded like it would be a paradise, and it really was: an early 16th house with beautiful bedrooms, enormous beams of glowing wood and huge baronial stone fireplaces.

It would have been wonderful to have had time to spend sitting in the garden. The weather when I arrived had been rainy although the early morning today was a different picture.

Natalie took me to meet her beautiful chickens, her pride and joy.

These ones are young yet and not great egg producers, but I got the feeling that it wouldn’t matter even if they never produced anything because the chickens are great family pets, like the two beautiful cats, mother and daughter.

There have been suspicions of foxes in the area and Natalie showed me the trap she had set: a great cage baited with jambon in which she hoped to catch the predator. Last time she had set it she caught a pine marten, and Stéphane had driven it 35 km to release it.

Supper was absolutely fabulous. In two weeks time Stéphane is taking an important cookery exam for which he has been preparing for more than a year, perfecting the techniques of French cuisine. If last night’s meal was anything to go by, he’s going to do very well. Good luck, Stéphane! I hope they ask you to reprise your chocolate mousse…

After doing some early morning gardening Natalie left for work at 9 o’clock, but Stéphane and I stayed chatting for ages over breakfast about the different school systems in the UK and France. Their originally Napoleonic educational system, Stéphane said, is still constructed on philosophically military lines, and it had been the lack of autonomy and the huge class sizes and the officious and inflexible inspection system that had eventually made Stéphane feel that it wasn’t for him anymore and he quit his job as a PE teacher.

Natalie hadn’t caught a fox last night in her trap, nor a pine marten. But we took some photographs out in the garden and it was so idyllic that I could hardly bear to leave.

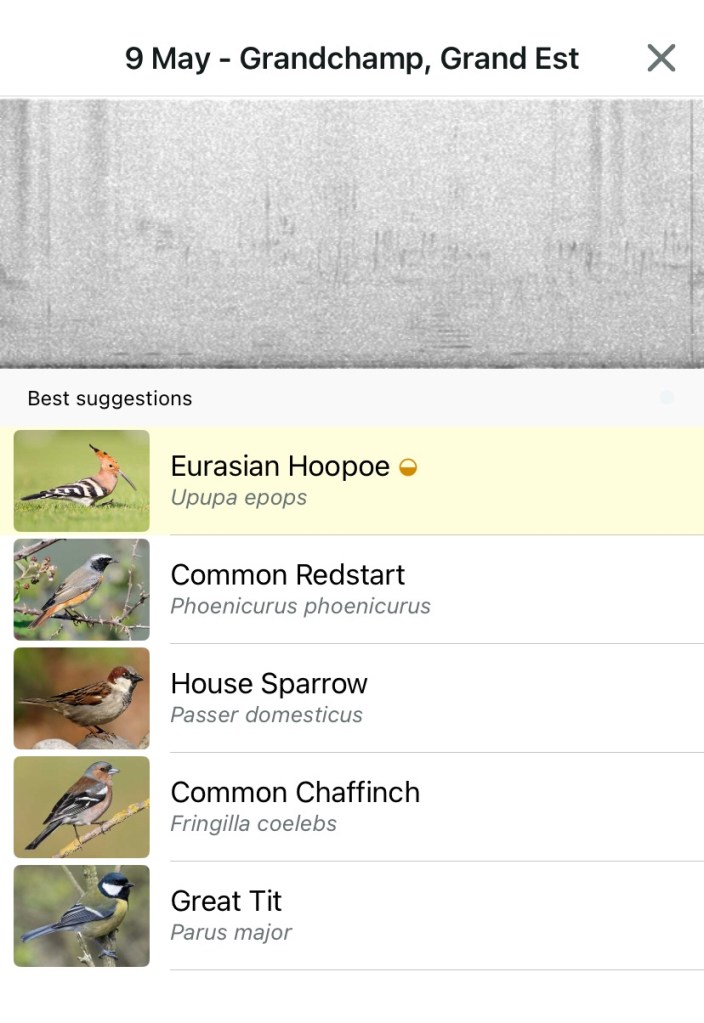

Out in the street there were no signs of yesterday’s bees, but the odd birdsong that I had heard yesterday started up again. I had my suspicions confirmed when I went down to the river and put the Merlin app on the case. The birds that I had seen yesterday and thought were jays and the regular whoop whoop whoop noises were being made by HOOPOES.

I was almost dancing with excitement! René and Peter were coming out of the house to do some work and I couldn’t not share with them the excitement of the fact. ‘Oh yes!’ said Peter. ‘I can hear it. A cuckoo.’ René said that was rubbish and started talking volubly to me in Dutchas though I could understand every word. I think he said he’d seen them on his back wall, with their extraordinary crests standing up. He offered me a cup of coffee, and in many ways it would’ve been wonderful to accept, but I had just had one, it was 10:30, and I really did need to get going.

Rather regretfully, I crossed back over the river, looking over the edge to see fat fish on patrol, and left the beautiful village to the hoopoes and the swallows, to the pine martens and the foxes.

The little back road to Maâtz had sun on the fields, stonechats in the trees and peace and quiet spread over everything. I caught myself still with an enormous grin on my face — the hoopoe effect — and although it was another road walk, I felt too happy to switch on my audiobook. I had the wind in my hair, and a lighter rucksack because I had finally, with regret but not misgivings, handed my old shoes to Stéphan to put out with the rubbish. They have done so well and carried me so far. But it was time.

Maâtz had a completely unpronounceable name and a lot to recommend it —although not as much as Grandchamps. It seemed more political: the signpost at the start of the village was supplemented with an announcement of a farmers protest on the 13th. Natalie had told me yesterday that she and Stéphan had moved here from not far from Brienne-le-Château, and whilst I had thought Brienne was noticeably down on its luck, she told me it was a much poorer area here, with low wages. Houses though were consequently very cheap, and I could pick one up for a song, she said. It’s clear that for small-scale agricultural producers life is as difficult here as it is in Britain. The ones who are making the money are the gigantic conglomerates, the Big Ag I saw in the north.

But there was a lot of love in this village. A lady said hello to me as she watered all the pots outside her house, doors into sheds had wooden heart-shapes cut out of them, and there was attention paid to the business of sitting out under trees in the shade in the heat of the summer, surrounded by scruffy, self-seeded gardens.

The village has been here since the 12th century, and it was sleepy and apparently forgotten by time. Its main street was called Paradise Road.

The next village, Coublanc, was much more substantial, with some immensely old buildings here dating from the first half of the 16th century.

Coublanc should have been the end of yesterday‘s stage, which I had finished early. I was glad that I had, and not just because it had even out the distances of the two stages, it was also a little bit big to feel as immediately home in as I had in Grandchamps. It too seemed still to be living in the past, in terms of some of its housing stock,

although when it came to the agricultural machinery, it was bang up to date.

My favourite detail from Coublanc though was a tiny letterbox marked as such, wide enough only for billets doux.

When I sat in the middle of the town to have a look at the map, a little white dog trotted by, almost the first I’ve seen which has not been tied up or in a garden barking at me.

I’d rather hoped it wasn’t going to be a dog which had escaped from somebody’s garden and wanted to follow me, but it was rather I who followed him, down a twisting old road of high stone walls,

and over a stone bridge made of huge limestone slabs, crossing the Resaigne river where it joined forces with the Salon.

I met the dog again right at the end of the village before my path took me out into the countryside. He had installed himself on his own front porch, and barked suspiciously at me. I had no idea on what errand he had been on, so far away at the other end of the village. A visit to the butcher, perhaps?

After a few days of walking, it was lovely to get back out into the countryside, following the Via Francigena once again over grassy farm tracks, through knee-high crops of wheat and head-high crops of oil-seed rape.

My only job was to make sure I did not tread on the portals of an underground ants’ nest, where the little workers were industriously going about their ant business.

I crossed the Salon river for the first time out in the countryside. It was shallow and green, with shoals of tiny fish hiding amongst the waterweeds. A pied wagtail hopping about on the stones flew up as I passed to flick his tail on a tree branch over the water.

I have now not only come into a new department, the Haute-Saône, but I have crossed the watershed. Before now all the rivers (bar the most recent Resaigne along which Grandchamps and Maâtz and Coublanc were all threaded like beads on a necklace) had flowed eventually into the Seine and out into the Channel, but now the rivers all drain into the Rhône and their waters flow into the Mediterranean. It felt like something of a watershed for me also.

As if to celebrate the fact, here was a new wildflower. One of my favourites: the first cornflower of the season. The flowers open with the sun and are gone by the late afternoon. They are renewed every day throughout the summer with a seemingly endless supply of buds.

In a field sown with alfalfa were more cornflowers, scarlet poppies and some leftover or self-seeded small brassica. The random scattering of red blue and yellow was immensely pleasing.

As my path dipped a runner came towards me up the hill, and I couldn’t tell whether he was grinning at me or grimacing. Perhaps a bit of both! I wonder whether he had just come from the next village, Leffond or from further afield.

I was puffing myself as I came up out of the dip he had run down and then come up to meet me, and I was grateful to be able to stop to admire a new orchid.

Really, there were a host of wildflowers. More scabious, more often than not with an insect on every flower, and columbines. A striking ribwort plantain with pinkish flowers stopped me in my tracks,

As did a tall, solitary wild salvia of some kind

But by this time Leffond was in view, its helmet-shaped bell tower announcing the presence of the village nestling among the woodlands in the Salon valley. As I came down the chemin blanc a little carillon sounded the half hour, a faintly ridiculous tinkling, like a child’s toy.

It was half way through the day and it seemed to me the perfect place to stop for lunch.

I picked a spot down by the river, and munched at the mini salamis I had bought a couple of days before, and the leftover tomatoes. They were more swallows and housemartins than I could count, and after a while of watching them I realised they were swooping under the spans of the bridge to collect wet mud in their beaks with which to build their nests.

I set off again, but didn’t get very far because I stopped to take a photograph of a sign saying ‘Mr. Henry’, for a friend of my acquaintance of that name.

The inhabitant of the house, Gael, asked me (very politely) what I thought I was doing, and when I explained he immediately got very enthusiastic about telling me all about the history of the house, which had been the old milkman’s (Mr Henry, I presume) where he made and sold butter and milk. He showed me the hooks where the milkman had hung up his prices, and the old chimney round the back, and the cavernous spaces inside that he was doing up all by himself to turn into a bar. I could almost see the vision. It was going to be Mexican themed. I said I thought it was something of a Grand Project — and he thought mine was too. We said goodbye wishing the other bonne courage and bonne chance and I set off one more.

And once more I didn’t get very far because two minutes down the road I was distracted by another lizard orchid. Another two of them, in fact. There was a chap strimming grass behind me, and I flipping hope he wasn’t going to chop the orchids. By the look of the leaves of the first one, it had already survived one brutal haircut this year.

On the one side of the track was a field of wheat, a few straggly cornflowers poking out which on closer inspection I could see had been sprayed with weedkiller and were shrivelling.

On the other was a huge expanse of wildflowers, with bright new generations of painted ladies, orange and yellow clouded yellow butterflies with black edges to their wings, two blue butterflies engaged in aerial combat. They were feeding off the scabious, the ox-eye daisies, the buttercups. One side of the road sterile, the other a haven for the insects that in turn the birds need. If you want birds, you must have insects and if you want insects, you must have wildflowers.

The river bent towards the path (or vice versa) at the site of an old mill which is being converted. It’s clearly someone’s home, so I didn’t want to trespass. Another walker on this path who had overtaken me in Leffond clearly didn’t have the same compunction, and I saw him on the property taking photographs of the watermill. I walked on by rather quickly.

Through the woods up a small rocky hillside, through more fields and meadows, and then the path came to Montarlot, where the Salon river was covered thickly with tresses of flowering pond-water crowfoot as it passed under the spans of the old stone bridge.

The little village look like it had recently suffered from an earthquake, and all the reconstruction money had arrived at once. There were roadworks, renovations, reconstructions. There was material and equipment everywhere.

This was the last stop before the day’s end at Champlitte. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect of the little town. I knew it had a massive Château in it, but little more than that. As I came up the steep approach to the town I could see the other walker gaining on me, so I quickened my step and ducked into the Château — which Natalie had told me last night was a museum.

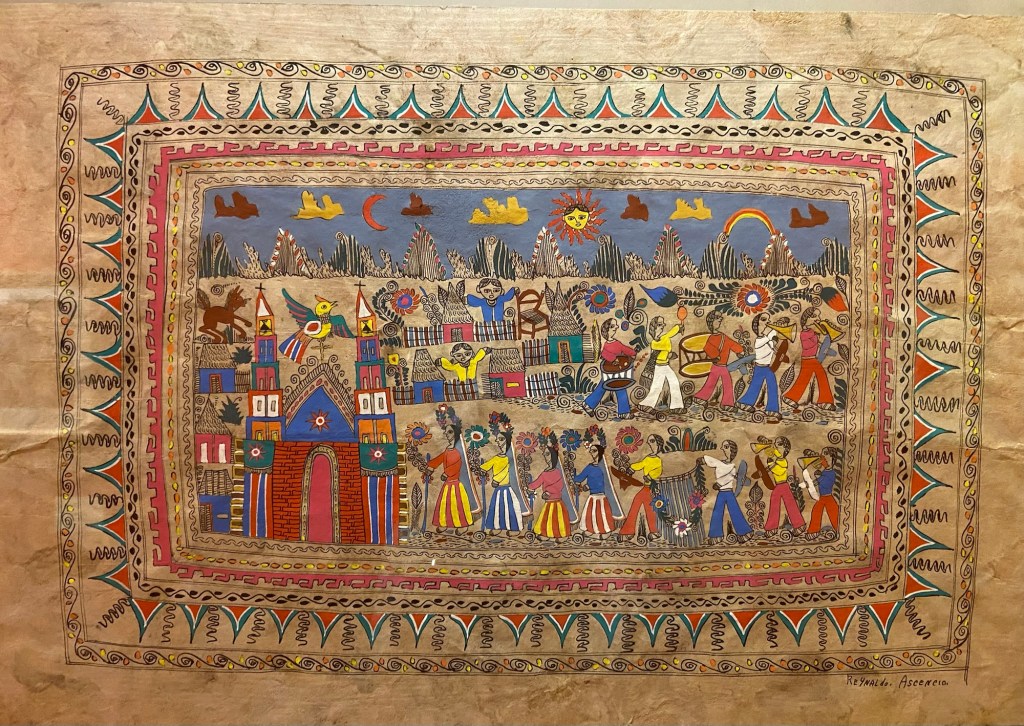

The best thing about museums is that you can take your rucksack off and put it in their cloakroom, which I did very gratefully, and then I set off round the special exhibition of Mexican life and customs.

Champlitte is twinned with a town in Mexico, and one of the first exhibits was a video of the twinning festivities, everybody dressed up in traditional Mexican and French costume with a lot of drinking and singing and dancing, the two mayors presiding. I had been told by Natalie to go to see the room with wallpapers of scenes of colonial Mexican life and I duly did — it made me think of the wallpapers of Indian jungle scenes I had toyed with putting in Oscar’s room (which needs a total transformation) in between the 17th century beams.

I didn’t much care for many of the permanent exhibits in the museum which were set pieces showing what an old pharmacy would’ve looked like, or a school, or a travelling fair with puppets and a small merry-go-round. It all seemed rather dusty. But the Mexican exhibits were wonderful: full of colour and energy. There were costumes, and 20th century artworks like this painting of a festival by Teynaldo Ascencio on plant fibre paper,

and these black and white photographs (I am kicking myself for not having made a note of who the photographer was — which is awful).

There was another room in which I just sat rather quietly resting in the coolth on a sofa. There was a video playing of Mexican farming life, but it was all in Spanish and I let it roll over my head.

A final piece was a work commissioned by a French artist to respond to the Mexican feast of the Day of the Dead. He had created figures of the ancestors, psychopomp figures whose job it is to accompany the newly departed soul to the afterlife. I loved the fusion of the French and Central American vision, a tangible response to the idea of twinning across cultures.

The museum didn’t have a stamp which could function as a pilgrim stamp, so I went to the Mairie and sat in a chair and waited for the functionary to finish her phonecall. This was the second time this had happened and it was vexing because it was completely obvious that she had no intention of helping me. Eventually, another chap came to use the photocopier and asked whether he could help, and it was the easiest thing in the world to get the stamp off the desk and do the necessary. Took half a second.

Outside, in the car park there was another swarm of bees — this one had settled in one of the municipal trees in a beautiful classic swarm shape. This (I thought) is the time of year when the old queen bees are ousted, and go travelling.

My AirBnB host for the night was a vigneron, a small-scale local wine producer for whom the gîte is a side hustle. I could see from way down the street a large sign saying ‘DÉGUSTATION’, which I took as a very good omen. Pascal was in a covered yard area by a sort of a garden, heating metal until it glowed in a small forge with a turning handle to pump in air and heat the coals red hot. He had a huge vintage anvil on which he hammered the metal flat. ‘I’m making a rose,’ he said.

Pascal’s Airbnb was providentially almost next to a well-stocked boulangerie which provided a quiche and a pizza slice for a carbohydrate- and fat-heavy supper. I also bought a fresh fruit tartlet because it counted as one of my five a day.

Pascal said I could come down at 6 o’clock and join in with a dégustation, so I duly presented myself at the door of the cave where a couple from Paris had been brought by a local friend to try the wines.

I did not recognise the names of many of the grape varieties: Auxerrois and Gewürztraminer. We tried three whites and a rosé, then two reds. The others bought four mixed half cases each, including some of Pascal’s sparkling wine, to take back to Paris. As they handed over wads of cash I crept away, thanking Pascale for my free wine. I was only sorry I can’t carry any wine with me!

Stats for the Day

Distance: 18.21 km

Time: 3 hrs 55 mins

Pace: a desultory 4.6 km/hr except for when I was trying to get ahead of the trespassing walker.

I love reading of your travels and the beautiful flowers and wildlife you see en route but best of all are all the wonderful different people you meet. So many great characters and interesting stories. Gina x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Engineer Gina!

LikeLike

😂 I have no idea where that comes from… I sign in with my email address and name! Engineer I might be… tech wizard I’m not!

LikeLiked by 1 person

WordPress thinks Clearly… you are! Haha!

LikeLike

I may be repeating myself because WordPress repeatedly asks me to log on, but I left a comment (which seems to have disappeared to me) to say that I loved reading all about your travels and the beautiful flowers and wildlife you see en route but best of all I like reading about all the wonderful people you meet. Such interesting characters and stories. Gina x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Huh. Several people have commented that outs happened to them. Most aggravating. Thank you for taking the trouble to comment twice!

LikeLike

Free wine is excellent wine, cheers! I get a lot of enjoyment out of reading about your food. Specially that which hails from the boulangeries. Can I riposte today with our nourishment after walking the Quiraing on Skye? A Cullen skink pie! Certainly a first for me, to have a dish commonly thought of as a hearty fish soup in a pie. But definitely one to recommend, specially after lots of vertical metres….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I shall ask for Cullen Skink in the mountains next week then!!

LikeLike

Paradise Road indeed! Hope the dégustation leads to a deep and restorative sleep.

I’m learning so much about natural history – and all from my chair. Delightful! Xx Vicki (aka differentcreative?!? I’ll embrace that…)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha yes — your nom de plume! I guessed it was you! Xxxxxx

LikeLike